BLANCO

CAPTURING HUMAN SUFFERING

PHILIPP DAGEN ( Art critic at Le Monde and Contemporary art Professor at La Sorbonne University)

To write about Stefano De Luigi’s photographs of blind people is not an easy task. It is difficult not to feel awkward. The immediate question is: what can be written that does justice to what is being presented here, right in front of our eyes? The subject matter is so extreme and uncompromising that formal considerations soon fall by the wayside and appear inappropriate and pathetic, the more so since De Luigi seems to shun such considerations.

So, let us make this abstinence the starting point. The depiction of human suffering in photography is one of the most substantial and dense subjects in the history of this art. It is also one of the most delicate since it raises the question, “How?”. We have seen hundreds of images – books and magazines are full of them – that are horribly cruel and perfect in their tragedy. The photographer is in complete control and masters it all with extreme precision: the framing, the lighting, the split second in which the shot is taken. There. He has obtained a very good image of misery.

The minute one uses the expression “a very good image of misery,” its meaning becomes ambiguous, to say the least. One can easily justify the photographer’s work by saying that the better the image, the more powerful the message and therefore, the stronger the sense of pity and anger in the viewer. On the other hand, the visual quality of the image can easily give rise to the suspicion of cultivating a certain style, aesthetic and rhetoric. Several wellknown photographers have widely published some very successful images of human misery, to the point that they have been accused of making it a speciality, or an industry like any other (and even of tampering with the images). If the suffering of his or her own kind becomes the subject of choice or the professional trademark of a photographer, the images become morally unacceptable and can only be seen as the spectacular product of a visual “charity business”.

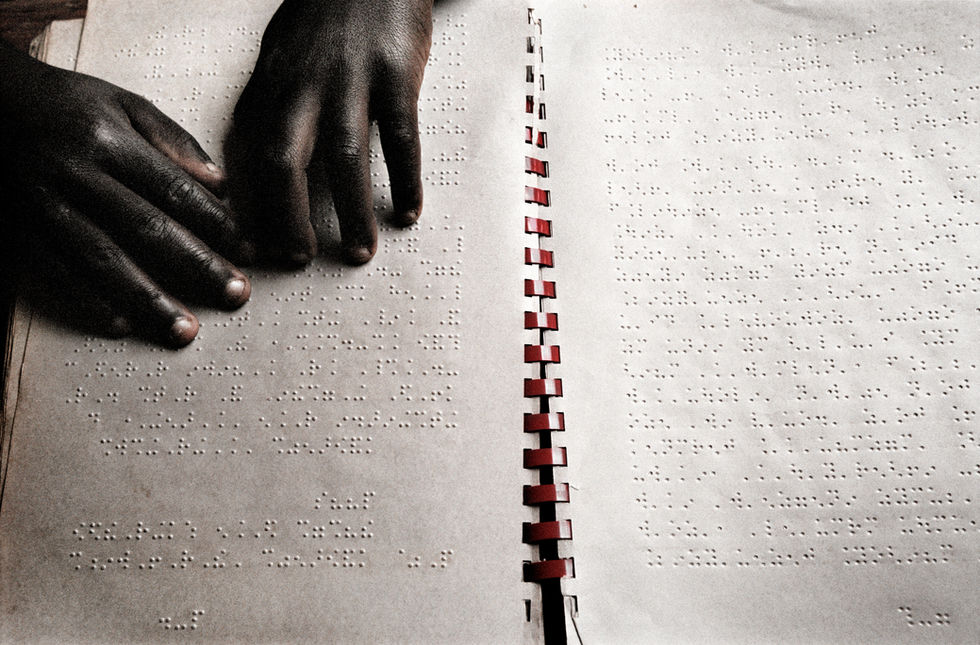

Such products soon stand out for what they are because of certain effects, elegant twists and stylistic affectations. De Luigi does not indulge in any of this. That is not to say that his images are not constructed, but in their composition, they shun both theatrics and a show of skill. More often than not, the faces are seen close up, head-on and in the foreground, bathed in bright, sometimes even raw light. De Luigi keeps the frames tight and does not let any props into the field. On some occasions he is so radical in the way he strips the composition right down that the work is not far from the constraints associated with identity pictures. He uses colour sparingly, and abstains from the kind of contrasted lighting that stirs and seduces. These could be seen as negative peculiarities: all the things he “does without” and all those he does not want. But the fact that he does without is essential. It would have been simple to draw a particular form of pathos from blindness. It is only too easy to imagine what others might have done, such as enhancing the shadows to work up the symbolism or focussing on emblematic gestures like a hand feeling its way or a grimace of despair, or the scars of decrepitude and picturesque exotic misery. Such has been the leitmotiv of Western photography.

The first time I heard about the series De Luigi was finishing on blind people, I was worried. What convinced me once I saw the work is that none of the things I have just mentioned are visible in it, quite the opposite. What is present is upright simplicity and rigorous focus. His photographs are not staged. Infinitely more violent is his way of confronting us with a presence. That is part of the reason why it seems so difficult to write about this work. There is nothing about it that commands commentary about formalism or aesthetics. The viewer is confronted with the subject stripped bare. It is impossible to evade.

The subject at hand is blindness, accidental or pathological. What is there to write or say about blindness that makes any sense? Perhaps it has something to do with superstition: for someone who spends his life looking – at people, photographs, paintings, sculptures, at what is known as art and what is said to be reality – it is close to impossible to contemplate the prospect of blindness. It would deprive him of everything, or if not everything, at least of what is essential to his life. One can imagine being struck by a number of illnesses or deprivations, to which one would get accustomed in time. But not blindness.

The truth is, some of these portraits are close to unbearable. The people who feature in these images will never see them. Whoever looks at them cannot begin to mentally place themselves in the position of the “models” – if one can even use that term in this instance. The viewer’s vision has no other subject than the absence of vision in the look of the blind person. All there is to see is what it means not to see. The only thing to do is to examine these eyes or sockets through which no vision ever passes. The clearer and brighter the photograph, the more one is aware of the fact that it is a privilege to be able to look at it at all, and that this privilege could be taken away or never have been granted at birth. Every image carries a warning or a threat. That is how powerful these photographs are. It is therefore hardly surprising that they become etched in our memory with an authority that seems remarkable given that we are saturated by images, consuming and absorbing enormous quantities of them but retaining very few, if any.

An image therefore needs to have a rare quality to stand out as an exception and not disappear in the daily flow that passes before us but leaves us with nothing. De Luigi’s photographs possess that distinctive quality derived from the fact that they are both rigorous and evident, two characteristics that cannot be disassociated.

One final brief remark. De Luigi is the author of a series of photographs about television, cinema and pornography. His works are concerned with image-making and the present-day fascination with images: this is the intellectual logic running through different components of his work. Each is a chapter in an ongoing analysis that focuses on visual representation and its various contemporary modes. De Luigi is a photographer who questions the power of the “visual”, the conditions under which it is used, and its limitations. This means that in photographing blindness, he has pushed his thinking to its most extreme point: the moment in which vision is abolished in solitary darkness. It is the moment in which there can be no more images, no more representation, no more “visuals”, no more of those things that make up the daily lives of people on this planet. The coherence in De Luigi’s body of work is remarkable.

PHILIPPE DAGEN is a writer, art critic of Le Monde, exhibition curator and Contemporary Art professor at the Sorbonne University. He lives and works in Paris.